Dedicated to promoting Southasian cinema, this American nonprofit founded by two women from marginalised communities in India has grown into an Oscar-qualifying film festival that attracts hundreds of high-quality Southasian films every year

By Shailaja Rao

When the programming committee for Tasveer Film Festival in Seattle, Washington, selected Delhi-based Shaunak Sen’s documentary feature film All That Breathes to screen at its 2022 edition, little did the organisers expect it would go on to earn an Oscar nomination the following year.

Over the last 21 years, Tasveer, which means ‘picture’ in Urdu/Hindi, has exhibited many trailblazing filmmakers long before they achieved international recognition.

This year, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences bestowed an Oscar-qualifying status on Tasveer, the largest and oldest Southasian* film festival in North America. This recognition places Tasveer on par with international festivals like Tribeca, Sundance, and Cannes. It is also the only Southasian film festival to have this honour.

The winning short film at the upcoming Tasveer Film Festival, taking place October 12-22, in-person and virtually, will become eligible to compete for next year’s Oscar awards.

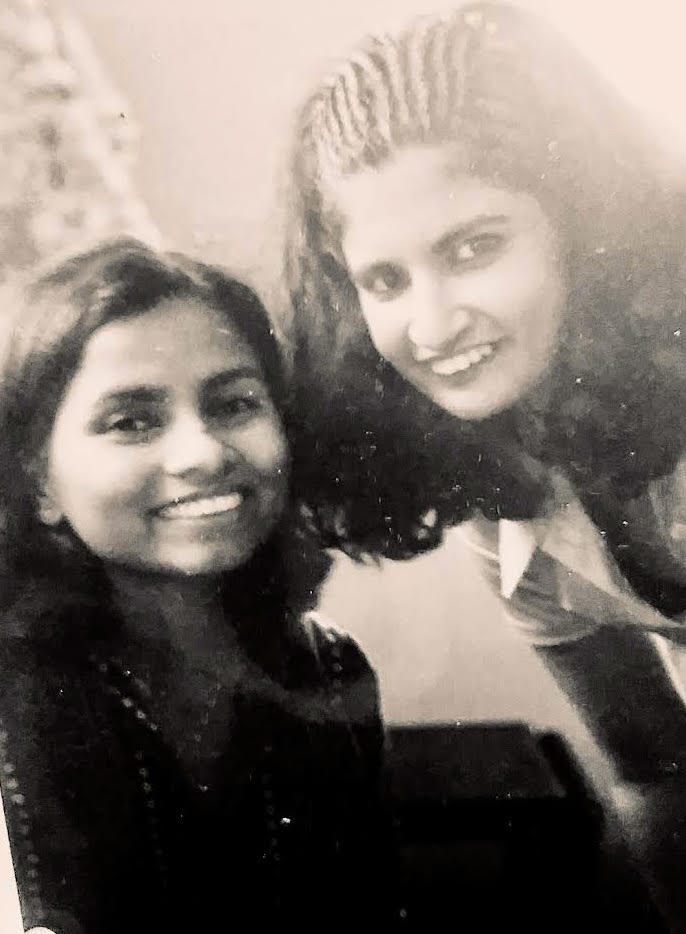

Behind these achievements are two women from India, both belonging to marginalised communities – Rita Meher and Farah Nousheen, who have been close friends since the summer of 2001, when they met by chance in an office lobby in Seattle, their adopted city. “Are you from India?” they recall asking each other when they first met.

The genesis

The two women came closer after the “9/11” attacks of 2001, as Arabs and people of Southasian origin became targets of hate crimes in America. Discrimination rose in workplaces, airports, places of worship, and other public places, with Muslims and Sikhs particularly under attack, a situation exacerbated by the Bush administration’s racial profiling.

“We did not have a seat at the table,” comments Rita, referring to a platform or space to share perspectives and commonly held biases.

Stung by the stereotypical images, misleading messaging, and being excluded from the mainstream media narratives, Rita and Farah created “their own table” – they launched Tasveer as a community-based group in March 2002.

I met them both early last year after quitting my IT job of 23 years and joining Tasveer as a volunteer. The more time I spent with them, the more curious I was to understand their story better.

Their approach is to use Southasian art, film, and storytelling to dispel misconceptions, uplift minority voices, create awareness, and allow for a glimpse into the lives of Southasians.

Mission possible

To broadcast Southasian content to global audiences, Rita set up TasveerTV in 2019. The first-of-its-kind online streaming platform, dedicated to independent Southasian content and creators, serves as a virtual theatre for audiences worldwide. During the COVID-19 pandemic, TasveerTV helped entertain its subscribers through lockdowns worldwide.

Among other endeavours, when Netflix denied their request for sponsorship, Rita requested funding instead, to which they agreed. This funding provided the base for the Tasveer Film Fund in 2020, helping independent Southasian filmmakers in the US to bring their stories to life.

“The more people we can help, the better,” says Rita.

With a five-fold increase in funding this year, her vision to support diaspora filmmakers expanded to include aspiring Canadian filmmakers to participate.

Tasveer’s first public event, in 2002, partnered with TrikoneNW, a community-based organisation that supports LGBTQIA+ Southasians. They screened the documentary film Summer in My Veins at a local bookstore. It was followed by a talk by author Ruth Vanita on her book Same-Sex Love in India, Queering India (Routledge, 2002).

This set the tone for more Tasveer-curated events aimed at amplifying marginalised voices and questioning the status quo. Past events have included discussions and screenings around India and Pakistan’s pursuit of nuclear weapons with Anand Patwardhan’s film Jung aur Aman (War and Peace) in 2003.

Noteworthy events have included the 2007 panel discussion with the acclaimed filmmaker Shyam Benegal on Alternative Indian Cinema: Gender, Justice, and Dissent. A talk by activist and writer Madhu Kishwar in 2008 aimed to raise awareness on domestic violence and dowry laws in India.

When Tasveer partnered with Travelling Film South Asia, bringing a curated edition of the Kathmandu-based biennale film festival to Seattle in 2005, one of the films screened was Tale of the Darkest Nights, taking up the violence of the 1971 India-Pakistan war.

Among the audience was Tasveer supporter and film buff Uzma Khan, an American of Pakistani origin. The film brought back poignant memories of a few family friends who were serving in the Pakistani army and went missing. They returned after five years when India swapped prisoners with Pakistan. Watching the film was also an “aha” moment for Uzma.

She recollects, “We never heard or read about the Bangladesh genocide while growing up.” Uzma realised films could also be a source of learning and not just entertainment. Tasveer’s cause for social justice stuck with her ever since.

Struggles

In its initial years, 2002-2009, when Tasveer was a grassroots community-based group, Rita clocked in odd hours to keep it running. In 2013, she took the leap, quit her day job, launched a nonprofit organisation, and devoted herself to Tasveer, with a monthly salary of $500. A dwarfish, closet-size room that could barely fit a desk became Tasveer’s first office space inside an office building in the city.

Their struggles have included the heartbreak of community events being stalled or scrapped.

One of these was the San Francisco-based South Asian Sisters’ Urdu-Hindi show Yoni ki Baat inspired by Eve Ensler’s Vagina Monologues. The Tasveer version ran for 14 years in Seattle. While immensely popular, the show got cancelled because some considered Yoni ki Baat not “inclusive enough”, as the context of bodies and sexuality was limited to women.

Another popular initiative, the TasveerLit Fest, was cut for lack of funds only after running twice, in 2019 and 2020. This was a series of discussion panels and workshops where community members could hear authors read from their writings and engage on issues on race, immigration, gender, sexuality, and politics shaping the lives of the Southasian diaspora

The COVID-19 pandemic brought its own set of challenges as well as opportunities to reinvent programming.

There’s also the perpetual struggle to raise funds for staff and programming. Although they are now in a better position, it remains an uphill task.

While retelling the Tasveer story at the recently held board retreat, Farah said she knew it was essential for events to “provoke critical thought and ideas” rather than being solely a source of cultural entertainment.

Always supportive of social justice issues, in 2020, Tasveer supported the Seattle city council to pass a resolution urging the Indian parliament to repeal the discriminatory law known as CAA-NRC that called for a national register of citizens and fast-tracking some migrants to India for citizenship, favouring members of other major religions but not Islam.

When Seattle passed the Anti-Discrimination Law on 21 February 2023, the first in the US, it marked a profound “coming out” moment for Rita herself. I was present at the Seattle City Hall when she took the mic and spoke up about her caste identity in public for the first time. Until then, she had concealed her background as ‘Adivasi’, an indigenous community in India, fearing discrimination.

And now, Rita’s idea for a Tasveer Art Center, a progressive, secular, and inclusive safe place that would house a state-of-the-art auditorium, filmmaker’s studio, art gallery, and a hall to hold up to 300 people among other cutting-edge facilities, is her latest dream project.

The time is ripe for Tasveer to “own a place and call it home,” believes Rita.

Having witnessed her tenacity and determination over the past couple of years, I believe that if anyone can push through to see Tasveer Art Center, she can.

Shailaja Rao is a social justice and peace activist based in Seattle and a contributing editor at Sapan News. She is also the board president of Tasveer.

*Southasia: Borrowing from Himal Southasian, Sapan uses ‘Southasia’ as one word, “seeking to restore some of the historical unity of our common living space, without wishing any violence on the existing nation-states.”

This is a Sapan News syndicated feature.

Published in:

- South Asia Monitor, How a South Asian film festival grew to an Oscar-qualifying cinema platform, 9 Oct. 2023

- American Kahani, Tasveer: How a South Asian Film Festival Grew to Be an Oscar-qualifying Cinema Platform, 11 Oct. 2023

- South Asia Union, How an unapologetically South Asian film festival grew to an Oscar-qualifying cinema platform, 13 Oct. 2023

Sapan News is an entirely volunteer-run initiative. If you like what we do, please consider supporting us with a donation to help us take this work forward.