The Pakistan Supreme Court recently ruled that Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was unjustly tried and executed, A similar case to be made to re-open the trial of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru, hanged in Lahore on 23 March 1931 – a story that continues to capture the imagination of rights activists and researchers in India, Pakistan and the Southasian diaspora

By Chaman Lal

I thought of the executed freedom fighter Bhagat Singh and his comrades recently when the Pakistan Supreme Court ruled, in response to a presidential reference filed 12 years ago, that ousted Prime Minister of Pakistan Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had been unjustly hanged in 1979.

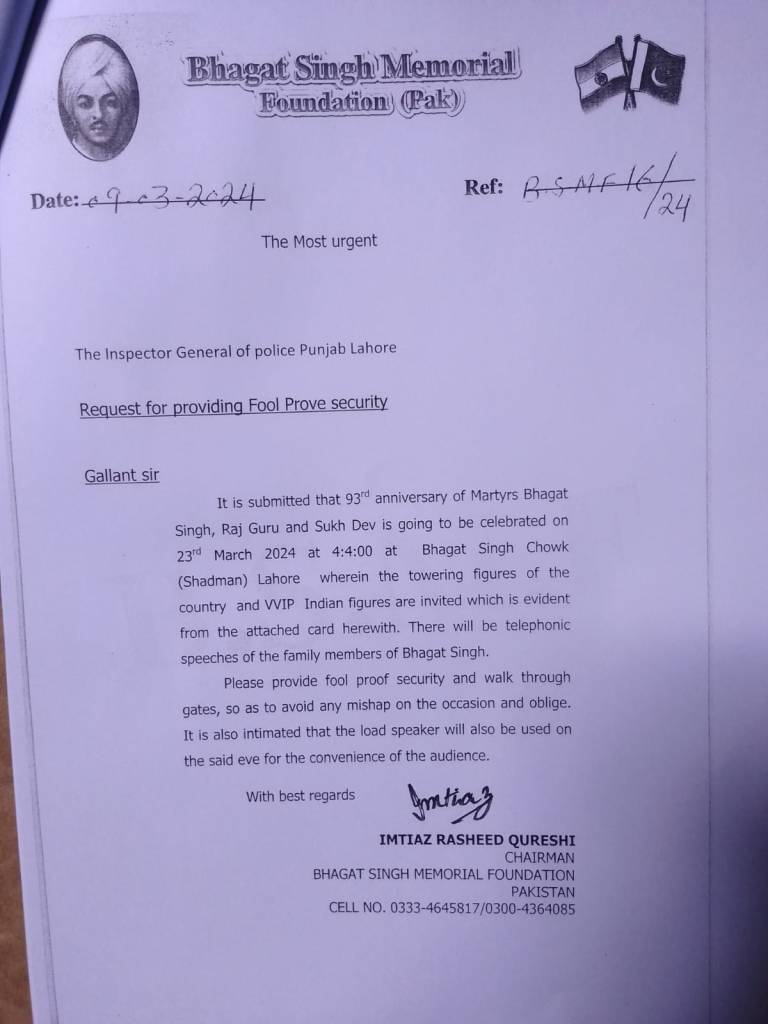

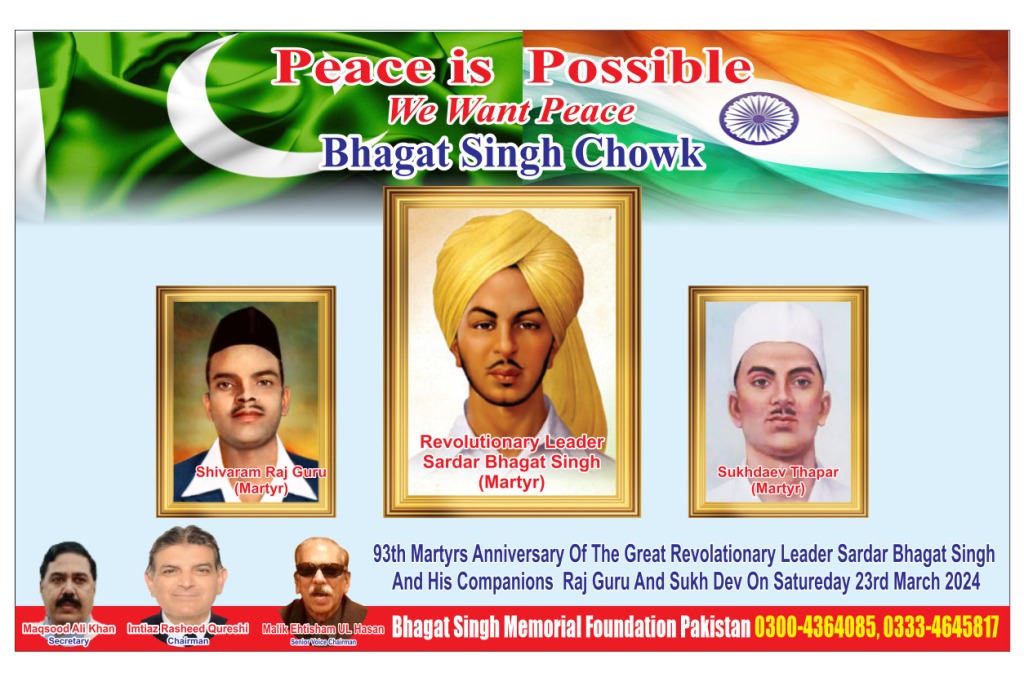

Over ten years ago, in 2013, my old friends in Lahore, advocate Abdul Rasheed Qureshi and his son Imtiaz, both senior lawyers of the Lahore High Court, petitioned the Lahore High Court to acquit Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar, and Shivaram Rajguru from the Lahore Conspiracy case.

They had founded the Bhagat Singh Memorial Foundation in 2010, pledging to take forward the memory of this son of the soil of Pakistan. Abdul Rasheed Qureshi passed away in 2021.

Imtiaz Rasheed told Sapan News that the Lahore Conspiracy case did not fulfill the requirements of justice as due process had not been followed. Bhagat Singh’s name was not even mentioned in the police report used as a basis for the case. It was also not brought before a trial court – which is also what happened with Bhutto. The three-judge tribunal hearing the Lahore Conspiracy case pronounced the death sentence without hearing the testimonies of as many as 450 witnesses, or giving the defendants a chance to appeal.

The entire judicial procedure was so defective that the respected writer A. G. Noorani terms it a ‘judicial murder’ (The Trial of Bhagat Singh: Politics of Justice, Oxford University Press, 2001).

Shared legacy

The Lahore High Court dismissed Imtiaz Rasheed’s case last year but the Supreme Court’s ruling on the Bhutto trial has encouraged Imtiaz Rasheed to file a similar petition. He plans to do this after Ramzan (Ramadan).

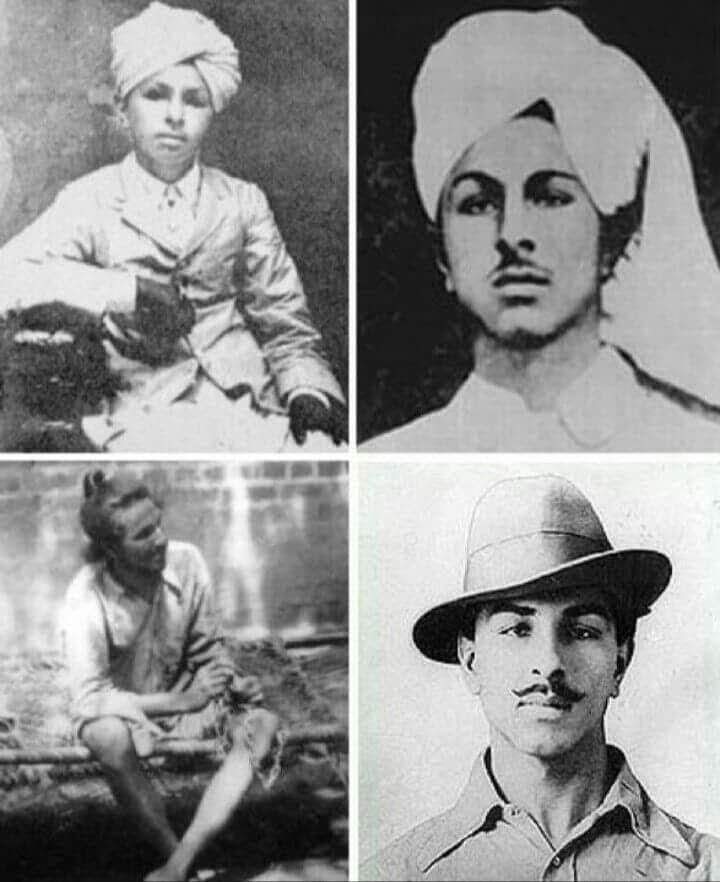

Bhagat Singh’s political influence began early as a follower of Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent approach to achieving independence from the British. But after years of watching the injustices of colonial rule, Singh became disillusioned with not fighting back and joined forces with other revolutionary figures.

Since 1947, the establishments of Pakistan and India have aggressively promoted identities of ‘separateness’ based on religion. However, the people of both countries have a more mature understanding of the fluidity of identities. The states don’t want to acknowledge identities other than the dominant ones, but many people on either side claim Bhagat Singh and his comrades as their own, a shared historical legacy that endures.

There are many examples of the cross-pollination of these ideas.

In 2007, Irtiqa, a progressive Urdu journal from Karachi marked Bhagat Singh’s 100 birthday by publishing a special issue highlighting poems and other materials about the man many see as a hero and martyr.

The volume included an essay by Zaheda Hina, the well known Urdu writer in Karachi describing Bhagat Singh as a ‘son of Pakistan’ – born in Lyallpur district, now Faisalabad, 28 September 1907, and executed and martyred in Lahore, 23 March 1931, both in what became Pakistan.

Civil society activists and groups gather at the spot annually on 23 March, to pay tribute to the martyrs.

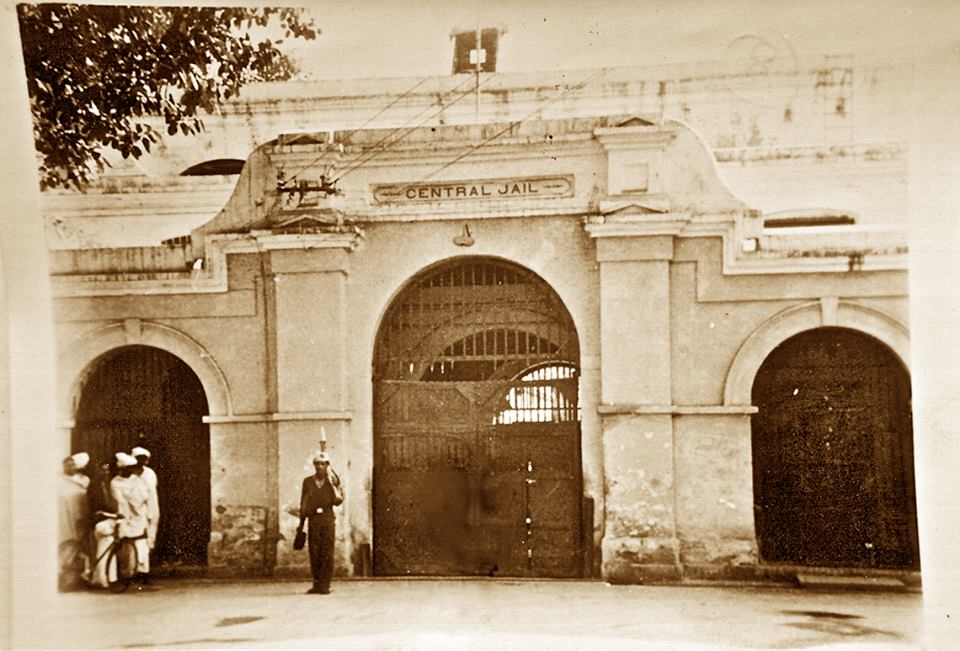

In response to consistent campaigning by Bhagat Singh’s supporters, following a public consultation, Lahore municipal authorities in 2012 agreed re-name Shadman Chowk, where the execution point of Central Jail once stood, as Bhagat Singh Chowk. Artist Salima Hashmi, daughter of the iconic poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz was part of the expert committee which made the recommendation.

A group of traders and clerics opposing the decision obtained a stay order from the Lahore High Court, so the decision was never implemented. Imtiaz Rasheed has filed a counter petition for contempt of court, urging that the order be implemented.

Facing threats and attacks from various extremist groups since 2013, the Bhagat Singh supporters appeal every year to the Lahore administration to be provided security.

The hanging

Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were hanged on the evening of 23 March 1931, at 7 pm. Normally, executions take place in the morning; these executions had already been planned for the morning of 24 March.

However, British colonial authorities, scared of a massive protest, advanced the execution by 12 hours.. As a protest on the evening of 23 March ended, the demonstrators heard about the executions and gathered at the gate of the Lahore jail.

A jail official revealed to an Indian nationalist living near the jail that the three had thrown off the black hoods that traditionally cover the faces of those being hanged, saying they were no criminals. Holding their heads high, shouting slogans of “Inqilab Zindabad” (long live revolution), the anti-imperialist activists strode to the gallows. (Decades later, Iraq President Saddam Hussain similarly threw off the black hood from his face before being hanged in 2006 on the orders of an Iraqi Special Tribunal).

The British authorities cut up the dead bodies, stuffed them into jute sacks, burnt them without proper rituals, and threw them into the Sutlej River near Ganda Singh Wala village. Locals, along with Singh’s younger sister Bibi Amar Kaur, Lala Lajpat Rai’s daughter Parvati Bai, who had followed the officials from Lahore jail, retrieved the half-burnt body parts and brought them back to Lahore for proper cremation rituals.

More than 50,000 people attended the funeral. There was also a huge gathering at Lahore’s Minto Park the next day, according to a front-page report in The Tribune of Lahore on 26 March.

Decades later, the interest in Pakistan and elsewhere about Bhagat Singh has only grown. In the pre-1965 war days, Indian visitors to Punjab, Pakistan, would invariably visit Chak No 105, Bhagat Singh’s birthplace.

With visa issues, the stream of visitors has dried up but the interest has only grown.

The Lyallpur Historian Club organises lectures on Bhagat Singh and celebrates his birth and death anniversaries annually in his place of birth.

The family allotted to Bhagat Singh’s birth home has created a two-room museum of the freedom struggle with pictures of freedom fighters of that period – Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims. During his tenure as India’s ambassador to Pakistan, TCA Raghvan also visited the house.

Famous Sindhi poet Sheikh Ayaz wrote an epic on Bhagat Singh in Sindhi. Punjabi poet Ahmad Saleem has a poetry collection titled Kehdi Maan ne Bhagat Singh Jammiya (Which mother gave birth to Bhagat Singh).

Che Guevara

Several books have been published about Bhagat Singh and more are in the works. Ammara Ahmad, a journalist and scholar is planning her research on Footsteps of Bhagat Singh in Lahore. Historian Waqar Piroz, who retired from Govt. College Lyallpur (Faisalabad), wrote an Urdu biography of Bhagat Singh, Sarfarosh Sardar Bhagat Singh (Fiction House, Lahore, 2023).

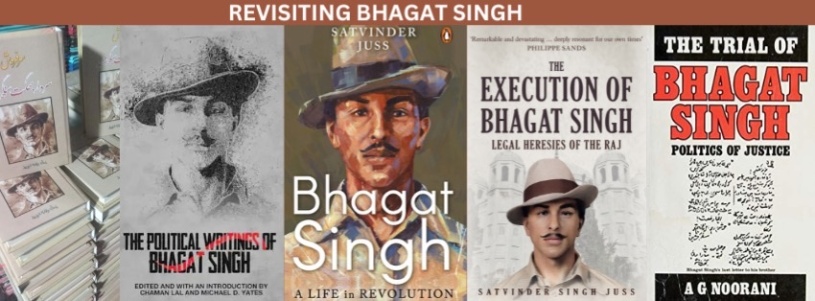

Two earlier books by British Indian scholar and lawyer Satvinder Juss contain valuable information, as he obtained access to study the 134 files of the Bhagat Singh case at the Punjab Archives in Anarkali, Lahore – The Execution of Bhagat Singh: Legal Heresies of the Raj (Amberley Publishing, UK, 2020) and Bhagat Singh Life and Revolution (Penguin India, 2022).

A Pakistani historian told me in 2014, that the Pakistan Government was planning to digitise these files and put them in the public domain. Ten years later, this has yet to happen. However, the Punjab Archives Lahore in 2018 did hold an exhibition on the Bhagat Singh case, exhibiting many documents from these files for the first time.

Monthly Review ex-editor and director Michael D. Yates and I recently co-edited The Political Writings of Bhagat Singh published by LeftWord India in December 2023, also being published by Review Press, New York, this year.

Bhagat Singh’s symbolism as a popular revolutionary international icon reminds me of Che Guevara, connecting the revolutionary traditions of Southasia and South America.

Chaman Lal is a leading authority on Bhagat Singh, and recently retired as a professor from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He is Honorary Advisor Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, Delhi Archives and has authored and edited several books on Bhagat Singh including The Bhagat Singh Reader (2019) and Understanding Bhagat Singh (2013). His compilation of the complete writings of Bhagat Singh has been published in Hindi, Urdu, English and Marathi. He runs the Whatsapp channel ‘Bhagat Singh Study’. Email Chamanlal.jnu@gmail.com.

Lead image: Compilation of some books on Bhagat Singh. Graphic by Regina Johnson

A Sapan News syndicated feature available for republication with due credit

NOTE: Updated captions in the slideshow of photos – the play on Bhagat Singh being performed is by the Indian playwright Davinder Daman.

Note on Southasia as one word: We use ‘Southasia’ as one word, “seeking to restore some of the historical unity of our common living space, without wishing any violence on the existing nation states” – Himal Southasian

Appreciated the story? Support non-profit journalism. Help us meet our costs. Make a tax deductible contribution to Sapan News

Thank You

Also published in:

- Mainstream – If the Z.A. Bhutto trial could be declared unjust, why not Bhagat Singh? – 23 March 2024

- South Asia Monitor – If Z.A. Bhutto hanging could be declared unjust, why not reopen hanging of Bhagat Singh and his fellow revolutionaries? – 23 March 2024

- Scroll.in – Why a Pakistani lawyer wants a court to retry the case that led to Bhagat Singh’s execution, 06 Apr 2024

- Crime Today News – Why a Pakistani lawyer want a court to retry the case that led to Bhaghat Singh’s execution,06 April 2024